Sietse M.Aukema, 1,2 Reiner Siebert, 3 Ed Schuuring, 1 Gustaaf W. van Imhoff, 2 Hanneke C. Kluin-Nelemans, 2 Evert-Jan Boerma, 1 and Philip M. Kluin 1 1 Department of Pathology and Medical Biology, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, The Netherlands; 2 Department of Hematology, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, The Netherlands; and 3 Institute of Human Genetics, Christian-Albrechts University Kiel and University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Kiel, Kiel, Germany

In many B-cell lymphomas, chromosomal translocations are biologic and diagnostic hallmarks of disease. An intriguing subset is formed by the so-called double-hit (DH) lymphomas that are defined by a chromosomal breakpoint affecting the MYC/8q24 locus in combination with another recurrent breakpoint, mainly a t(14;18)(q32;q21) involving BCL2. Recently, these lymphomas have received increased attention, which contributed to the introduction of a novel category of lymphomas in the 2008 WHO classification,“B-cell lymphoma unclassifiable with featuresinter mediate between DLBCL and BL.” In this review we explore the existing literature for the most recurrent types of DH B-cell lymphomas and the involved genes with their functions, as well as their pathology and clinical aspects including therapy and prognosis. The incidence of aggressive B-cell lymphomas other than Burkitt lymphoma with a MYC breakpoint and in particular a double hit is difficult to assess, because screening by methods like FISH has not been applied on large, unselected series, and the published cytogenetic data may be biased to specific categories of lymphomas. DH lymphomas have been classified heterogeneously but mostly as DLBCL, the majority having a germinal center phenotype and expression of BCL2. Patients with DH lymphomas often present with poor prognostic parameters, including elevated LDH, bone marrow and CNS involvement, and a high IPI score. All studies on larger series of patients suggest a poor prognosis, also if treated with RCHOP or high-intensity treatment modalities. Importantly, this poor outcome cannot be accounted for by the mere presence of a MYC/8q24 breakpoint. Likely, the combination of MYC and BCL2 expression and/or a related highgenomic complexity are more important.Compared to these DH lymphomas, BCL6 ? /MYC ? DH lymphomas are far less common, and in fact most of these cases represent BCL2 ? /BCL6 ? /MYC ? triple-hit lymphomas with involvement of BCL2 as well. CCND1 ? /MYC ? DH lymphomas with involvement of 11q13 may also be relatively frequent, the great majority being classified as aggressive variants of mantle cell lymphoma. This suggests that activation of MYC might be an important progression pathway in mantle cell lymphoma as well. Based on clinical significance and the fact that no other solid diagnostic tools are available to identify DH lymphomas, it seems advisable to test all diffuselarge B-cell and related lymphomas for MYC and other breakpoints. (Blood. 2011;117(8):2319-2331)

Introduction

Approximately 40% of all B-cell lymphomas are characterized by the presence of a recurrent reciprocal chromosomal translocations. 1-5 In most cases an oncogene is deregulated by juxtaposition to an enhancer of the immunoglobulin (IG) loci, whereas promoter substitution or fusion of genes leading to fusion proteins are less frequent. Certain translocations are characteristic for a specific type of lymphoma and are often considered as cancer-initiating events. For instance, irrespective of being endemic, sporadic, or AIDS associated, the t(8;14)(q24;q32) or variant translocations involving the immunoglobulin light chain loci, are considered as the lymphoma-initiating event in Burkitt lymphoma (BL), constitutively activating the MYC gene. However, similar MYC breakpoints may also occur as secondary events during disease progression in other lymphomas. These secondary events can occur metachronously after a clinically evident phase of indolent lymphoma or synchronously at the moment of clinical presentation.

Lymphomas with recurrent chromosomal breakpoints activating multiple oncogenes, one of which being MYC, are often referred to as “Dual Hit” or “Double Hit” (DH) lymphomas. Rigorously, DH lymphoma is a rather imprecise term because, from the nomenclature point of view,it is neither restricted to B-cell lymphomas(eg,inv(14)-positive T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia may carry a MYC translocation) nor does it exclude 2 translocations activating oncogenes other than MYC (eg, a follicular lymphoma with simultaneous BCL2 and BCL6 translocation). Nevertheless, the term DH lymphoma is mostly used for mature-B-cell lymphomas with a chromosomal breakpoint affecting the MYC locus. For clarity, we will through the text apply a nomenclature, including the affected oncogenes, for example, BCL2 ? /MYC ? , and use the term DH lymphoma for all cases with multiple recurrent breakpoints (triple/quadruple) as well.

Because cases with a MYC/8q24 and BCL2/18q21 breakpoint (BCL2 + /MYC +DH lymphoma) are most common, these casesreceived most attention in the literature. In particular a subset of aggressive lymphomas in elderly patients, previously often diagnosed as Burkitt-like lymphoma, aggressive B-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified (NOS), or diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCL), appear to represent such DH lymphomas. In the updated classification for malignant lymphomas by the World Health Organization (WHO), it is proposed to classify most if not all cases as “B-cell lymphoma unclassifiable with features intermediate between DLBCL and BL.” 6 This novel category is meant to create a (temporary) container for aggressive mature B-cell lymphomas that should not be diagnosed as either BLor DLBCL.

DH lymphomas make up an important part of this novel WHO category, the other part representing heterogeneous cases of aggressive B-cell lymphoma that have features of BL such as a monomorphic proliferation of blasts and a very high proliferation rate, often in combination with a germinal center (GC) phenotype (CD10 + , BCL6 + , MUM1/IRF4 + ). The latter lymphomas contain a MYC breakpoint in 30%-50%, an incidence that is higher than seen in regular DLBCL (10%) but considerably lower than in regular BL (90%-100%). In this review we focus on DH lymphomas as follows. (1) First, we explore the published cytogenetic data for the presence of known and novel recurrent chromosomal abnormalities in DH lymphomas. (2) The biologic function of the involved oncogenes in these lymphomas is briefly discussed. (3) We discuss the timing of the occurrence of the breakpoints in lymphoma genesis as well as the synergistic action of the involved oncogenes. (4) The pathologic and clinical aspects of BCL2 + /(BCL6 + )/MYC + DH and triple hit (TH) lymphomas are reviewed. (5)Ashort section is devoted to other DHB cell lymphomas.(6)Therelationship with “B-cell lymphoma unclassifiable with features intermediate between DLBCL and BL” is discussed. (7) Finally, we draw conclusions and formulate recommendations.

Published DH lymphomas

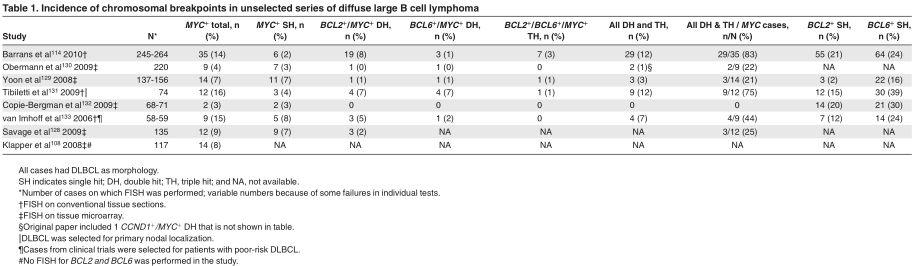

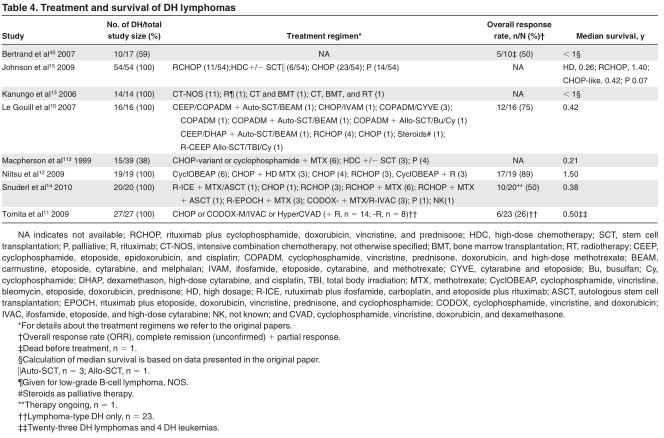

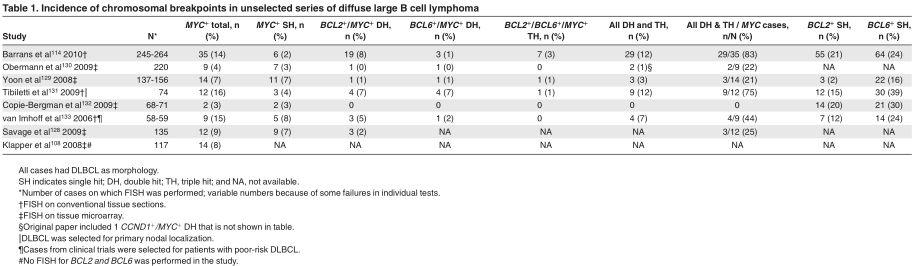

To get an impression on the incidence of MYC breakpoint positive and DH lymphomas diagnosed as DLBCL, we analyzed the available fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) studies on series of unselected DLBCL for the presence of the most common chromosomal breakpoints. Table 1 shows the results from 8 larger studies, 3 being incomplete with respect to BCL2 and BCL6. These studies show a wide range of MYC breakpoints in 3%-16% of the cases and DH lymphomas in 0%-12%. The wide range of BCL2 breakpoints and therefore also DH cases may be partially because of the inclusion of one series from Asia in which the incidence of t(14;18)–carrying lymphomas may be lower than in Western countries. 7

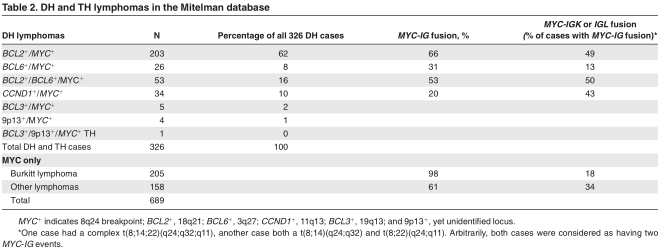

FISH analysis only informs on the targets for which probes are used.To get a better idea about the nature of all DH lymphomas and to search for other types than BCL2 + /MYC + and BCL6 + /MYC+ lymphomas, we explored the Mitelman Database of Chromosome Aberrations in Cancer, edition February 2010 (see supplemental Tables 1-2, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). 8 This large publicly available database contains virtually all published cytogenetic data on a wide variety of malignancies, including B-cell lymphomas. We selected reports with a MYC breakpoint published after the Revised European-American Lymphoma classification to be confident about the classification of the cases. 9 We realize that this has introduced a certain bias toward DH lymphomas, because several of these publications specifically addressed this phenomenon. 10-15 We included only mature B-cell malignancies (see supplemental data for strategies and sources). Plasma cell neoplasms were excluded because they represent a different disease and are characterized by genetic aberrations different from those seen in aggressive B-cell lymphomas. Translocations in myelomas involve both primary translocations(CCND1,CCND3,FGFR3 and MMSET, c-MAF, and MAFB) and secondary translocations involving MYC. 16,17 DHs involving these genes and also combinations thereof were frequently seen in the Mitelman database (5%-25%; data not shown). 8 Of note, a selection bias may have occurred because myelomas with MYC translocations probably have a higher success rate for culturing and karyotyping. Plasmablastic lymphomas were also excluded. A recent report identified MYC rearrangements in 49% of these lymphomas but no concomitant rearrangement of BCL2, BCL6 or PAX5.

From the 689 MYC + breakpoint–positive lymphomas 326 were DH lymphomas (47%). From the 804 cases diagnosed as DLBCL, 139 cases had a MYC breakpoint (17%).This incidence was similar to that reported for the period 1980-1995 (16%; data not shown). However, although between 1995 and 2009, 109 of 804 DLBCLs were BCL2 +/MYC +or BCL6 + /MYC +DH cases (14%), only 12 of 445 similar DH DLBCLs were reported in the period before 1995 (3%; data not shown). As stated earlier, this increase in the fraction of DH lymphomas after 1994 may be due to a growing interest in these lymphomas, as well as by changes in classification.

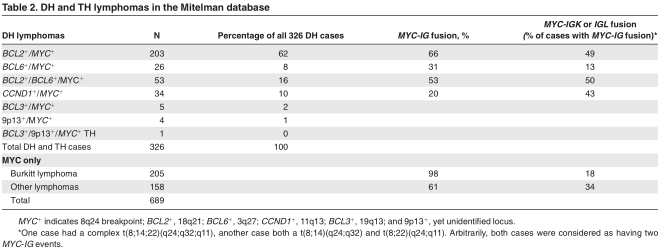

Taking these limitations into consideration, BCL2 + /MYC +DH lymphomas formed the great majority of DH lymphomas (62%; Table 2). BCL6 + /MYC + DH lymphomas were relatively rare (8% of all cases), and in fact TH lymphomas that involved MYC, BCL2 and BCL6 (16%) were more frequent than BCL6 + /MYC + DH cases. In DLBCL, 25 of 139 cases (18%) had a BCL6 breakpoint, whereas 84 of 139 (60%) had a BCL2 breakpoint (see supplemental Table 1). This preference for BCL2 + /MYC + is at least partially because of an underrepresentation of BCL6 breakpoints in the database, because these breakpoints at the very tip of chromosome 3 may have been missed by conventional cytogenetics. However, a very strong preference for BCL2 involvement in DH lymphomas was also found by FISH (Table 1) and suggests a selective complementary role for MYC and BCL2.

CCND1 + /MYC + DH lymphomas (N = 34) formed 10% of all cases. In fact, 5% of all mantle cell lymphomas (MCLs) in the database were CCND1 +/MYC + DH cases. Other recurrent DH lymphomas were 5 BCL3 + /MYC +cases with t(14;19)(q32;q13), 4 cases with t(9;14)(p13;q32) involving a yet unidentified locus on 9p13, 19,20 and 1 case with all 3 loci involved. A MYC breakpoint without any other recurrent breakpoint (MYC +SH) was seen in 363 of 689 cases (53%), from which 205 cases (56%) were diagnosed as BL(supplemental Table 1).

Although in typical BL MYC is almost always juxtaposed to an IG locus (in our dataset 98%), this was only found in 66% of BCL2 + /MYC +DH lymphomas (Table 2). Moreover, in 49% of the cases with juxtaposition to an IG locus one of the IG light chain genes was involved, which is far more than the 18% in BL. We explored the direct partners of MYC in the other DH lymphomas. Interestingly, in the group of BCL2 + /BCL6 +/MYC + DH lymphomas the commonest non-immunoglobulin partner was 9p13 (N = 19; 7%). This translocation was never seen in the BCL6 + /MYC + DH and CCND1 + /MYC + DH groups. Other recurrent translocations in the BCL2 + /MYC + group were t(1;8)(p36;q24) in 5 cases and t(2;8)(p11;q24) in 5 cases, the latter probably representing MYC-IGK fusion. Both in the BCL6 + /MYC + DH and BCL2 + /BCL6 + /MYC + TH groups BCL6 itself was a MYC partner in 4 and 7 cases, respectively.

oncogenes involved in DH lymphomas.

MYC

MYC is a transcription factor controlling the expression of a large set of target genes involved in cell cycle regulation, metabolism, DNA repair, stress response, and protein synthesis. 21 MYC exerts its function by dimerization with MAX and subsequent binding to specific consensus DNA sequences (CACGTG) called an “E- Box.” 22-24 Many genes are directly (de)regulated by MYC, including LDH-A and TERT. 25 In addition MYC is involved in the regulation of micro-RNA (miRNA) expression, 26-28 (de)regulating many target genes in an indirect way as well. Interestingly, MYC represses many miRNAs, which corroborates the idea that MYC generally is an activator of other genes. MYC expression in the GCs is, surprisingly, lower compared with naive and memory B cells. 29 This low expression could protect against MYC-induced genomic instability in the GC. For a detailed review about the role of MYC in lymphomagenesis, see Klapproth and Wirth. 30 Genomic alterations of the MYC gene include chromosomal translocations, mutations affecting regulatory sequences and promoter regions, as well as copy number increase. In contrast to early reports, most chromosomal breakpoints that involve MYC and the IGH locus are mediated by activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AICDA) and not by recombinase activating gene 1/2 (RAG1/2). 31-34 Thus, these breakpoints should have their origin from erroneous somatic hypermutation or class switch recombination. 35 On the basis of transgenic mouse models, additional factors are needed for malignant transformation. 36,37 This is supported by the finding that For personal use only. on May 23, 2018. by guest www.bloodjournal.org From MYC IG translocation can be detected in nonneoplastic conditions, both in humans and mice. 38,39 The mechanism responsible for translocations affecting MYC and non-IG loci, for instance 9p13 in the t(8;9)(q24;p13) translocation, is unknown. 15,40

BCL2

BCL2 was first described in the early 1980s by its involvement in the t(14;18) in follicular lymphoma. 41 As a member of a large BCL2 family of proteins, it has potent antiapoptotic functions. BCL2 is widely expressed in immature B cells and memory B cells but is temporarily downregulated in GC B cells, partially because of repression by BCL6. 29,42-44 With the occurrence of t(14;18), transcription of BCL2 is “constitutively” deregulated with high transcription activity from the translocated BCL2 allele. 42,45 This leads to a survival advantage of the involved B cells. Recent research has shown that BCL2 overexpression in B cells also leads to impaired DNA repair by blocking nonhomologous end-joining activities of Ku proteins essential for repair of both RAG1/2- and AICDA-mediated breakpoints. 46

With the exception of rare cases, 47 t(14;18) translocations are thought to occur early in B-cell development. 48,49 Chromosomal breaks are mediated by RAG1/2, probably in combination with low levels of AICDA. 50 Extensive mapping studies of the breakpoints as well as sequence analysis have shown that the BCL2 breakpoints are strongly clustered at cytosine-phosphate-guanosine (CpG) islands. One hypothesis is that these CpG island are first deami- nated by low levels of AICDA and that the resulting T:G mismatches are subsequently targeted by RAG1/2. 50 An in-depth discussion about the occurrence of the t(14;18) at later stages of B-cell development (including even the GC) and (secondary) involvement of RAG1/2 and/or other mechanisms herein 51-54 goes beyond the scope of this review.

Apparently, the t(14;18) is insufficient to cause follicular lymphoma because IGH-BCL2 transgenic mice do not develop lymphomas, and t(14;18)-carrying mature B cells can also be found in healthy persons and probably arise by the same mechanisms. 51,55-59 Hence, the translocation may rather facilitate than directly cause malignant transformation. The secondary genetic changes responsible for development into follicular lymphoma are not known. Importantly, these t(14;18)-carrying B cells in healthy persons, called “follicular lymphoma-like B cells,” usually enter the GCs, undergo somatic hypermutations and a limited degree of immunoglobulin gene class switching, and circulate as memory B cells. 60,61 This passage across the GC cell reaction with exposure to high levels of AICDA may make these cells susceptible for additional genomic alterations such as a MYC or BCL6 mutations and breakpoints. Thus, BCL2 ? /MYC ? DH lymphomas may arise in 2 ways: either they arise from a clinically overt or subclinical follicular lymphoma or they directly arise from the much more prevalent B cells with a t(14;18) that otherwise had not attained any malignant potential (Figure 1). Under both circumstances MYC translocation may function as a progression event, 48,62,63 although some follicular lymphomas with MYC breakpoints but without evidence of morphologic transformation have been described (see “Classification”).

BCL6

BCL6 is a zinc finger transcription factor with an N-terminal POZ domain. The gene is localized at 3q27, a position at the very end of the chromosome. BCL6 is widely expressed in many tissues, but in B cells it is mostly restricted to GC B cells. 64,65 BCL6 is required for the formation of GCs because mice deficient for BCL6 lack these structures. 66,67 Within the GC BCL6 acts as an transcriptional repressor of many target genes involved in apoptosis, DNA- damage response, cell cycle control, proliferation, and differentiation. 68-70 Important direct targets are BCL2, TP53, IRF4, and BLIMP1, the latter being essential for maturation into plasma cells. 71,72 Interestingly, BLIMP1 is a repressor of both BCL6 and MYC in plasma cells. As a result of the BCL6-mediated repression of TP53, 73 somatic hypermutation and class switch recombination are facilitated. Interestingly, the AICDA-mediated somatic hyper- mutation machinery can target many non-IG genes, including BCL6 itself. By facilitating activating mutations or chromosomal translocations, BCL6 activation may therefore indirectly lead to its own mutation and constitutive activation. 74,75 Deregulated expression of BCL6 in a mouse model that mimicks BCL6 translocations resulted in lymphoproliferative disease and ultimately in a disorder resembling DLBCL. 76 Only half of the translocations involving BCL6 affect an IG locus; in other cases the translocation partner is very diverse. Translocations involving BCL6 can be found in ? 30%-40% of all DLBCLs, some follicular lymphomas, and even some marginal zone B-cell lymphomas.

CCND1

The gene encoding cyclin D1 (CCND1) is located on 11q13 and is involved in cell cycle progression from the G 1 to the S phase, by forming a complex with CDK4 and activating the RB1-E2F1 complex, allowing E2F1 to be released. Although CCND2 and CCND3 are expressed in normal B cells, CCND1 is not. In consequence, CCND1 is almost exclusively expressed in neoplastic B cells with genetic alterations of 11q13, that is, translocation or copy number increase. In most MCLs and in a substantial fraction of multiple myelomas 11q13 translocations are observed. 77-80 In addition to these malignancies, also hairy cell leukemia and some cells in the proliferation centers of chronic lymphocytic leukemia as well as extremely rare DLBCL cases may express CCND1, the mechanism being unknown. 81 Like the t(14;18), the t(11;14) in MCL is mediated by RAG1/2, probably in combination with low levels of AICDA as well as other mechanisms. 50,82 Similar to the t(14;18), also CCND1 breakpoints are strongly centered at CpG islands, indicating a concerted action of AICDA and RAG1/2 in precursor B cells. 50 As seen for the t(14;18), also occasional t(11;14) ? cells can be found in the blood of healthy persons, however at much lower frequencies than t(14;18) ? cells. 83 This low frequency may be because these cells are not expanded in the GC cell reaction. This fits with the finding that MCL represents a pre-GC B-cell lymphoma. Of note, the t(11;14) in myeloma has a different configuration of the breakpoint with strong indications of an AICDA-mediated breakpoint initiated in GC B cells. 84

BCL3

BCL3 is a distinct member of the I κβ protein family and resides on 19q13. Its expression is dependent on the stage of B-cell differentiation with higher expression in mature than immature B cells. 85 Experiments in BCL3-deficient mice have shown that the gene is involved in GC formation. 86 The t(14,19)(q32;q13) leads to increased BCL3 transcription and has been described in a large variety of lymphomas and leukemias, 87 including atypical chronic lymphocytic leukemia. 88,89 Analysis of t(14;19) breakpoints indicates that this translocation is mediated by illegitimate class switch recombination. 90-92 E μ -BCL3 trans- genic mice overexpressing BCL3 show lymphoid hyperplasia but do not develop lymphomas. 93

Timing and synergy of translocations in DH lymphoma

DH mature B-cell lymphomas are by definition characterized by a MYC breakpoint in combination with another recurrent chromosomal breakpoint. Most MYC breakpoints are probably mediated byAICDAin mature B cells. In contrast, and with the exception of CCND1 in myeloma, BCL2 and CCND1 breakpoints are most probably mediated by RAG1/2 in precursor B cells. This strongly suggests that the MYC/8q24 breakpoint is a secondary event in the cases with a BCL2/18q21 or CCND1/11q13 breakpoint (Figure 1). This sequence of events is also supported by the fact that ~ 5% of all follicular lymphoma with a BCL2/18q21 breakpoint will acquire a MYC/8q24 breakpoint during the course of the disease and that at the cytogenetic level incidental cases show ≥ 2 subclones, one with only a t(14;18) and the other with both translocations. 48 Another argument for the secondary nature may be that, in comparison to the “primary” MYC breakpoints in BL whereby 82% affect the IGH locus at 14q32 (Table 2), many more of these “secondary” breakpoints affect the light chain loci. Probably, tumor cells still require a functional heavy chain protein for signaling and cell survival, because cells with disruption of both IGH alleles are deleted. 94

For BCL6 + /MYC +and BCL3 +/MYC + DH lymphomas the timing of events is less clear because most breakpoints affecting MYC, BCL6, and BCL3 are probably mediated by the same mechanism.

As shown in Table 2 there are interesting differences between BCL2 + /MYC + DH and CCND1 +/MYC + DH lymphomas with respect to the partner of the MYC gene. These differences might shed light on the mechanisms causing the MYC breakpoint. In the majority of the BCL2 + /MYC +DH lymphomas (66%) the MYC partner is an IG locus, which might reflect a high activity of AICDA that can induce mutations and breakpoints in both the IG and MYC loci. This may be because the t(14;18) translocation forces tumor cells to accumulate as GC B cells in which high AICDA levels are present. Exposure to high levels of AICDA may then lead to a MYC-IG breakpoint. In contrast, in CCND1 + /MYC + DH lymphomas MYC is in only 20% of the cases joined to an IG locus (see also Table 2 and supplemental Table 2). Indeed, the t(11;14) translocation does not result in accumulation of GC B cells because the tumor cells are already blocked in an earlier stage of development. Likely, the occasional MYC breakpoints without an IG partner in these cases are not caused by AICDA or by AICDA expression in extrafollicular B cells. What could be the biologic synergy of acquiring 2 or 3 breakpoints, and thus activating both oncogenes? This is again most evident for BCL2 and MYC whereby BCL2 is antiapoptotic without mediating proliferative signals.Instead,MYC drives the cells in an active proliferative and metabolic state,for instance by allowing anaerobic glycolysis in an anaerobic state by up-regulating lactate dehydrogenase A. 25 Moreover, in normal cells MYC induces DNAstress and activates the TP53 checkpoint leading to apoptosis; in consequence tumor cells with constitutive MYC activation frequently have acquired inactivating TP53 mutations or other mechanisms to protect them from apoptosis. In that view a preexistent BCL2 activation may also protect the cells from apoptosis.This synergy may be further enhanced by the fact that BCL2 can also repress important proteins involved in repair of non–homologous end joining–mediated DNAdouble-strand breaks. 46 When cells carrying a t(14;18)(q32;q21) enter the GC, this might facilitate an increased accumulation of chromosomal abnormalities, including MYC translocations , as a result of the processes of somatic hypermutation and class switch recombination. In that respect it would be interesting to study whether a combination of MYC and BCL2 translocation favors a molecular signature of genomic instability and therefore could explain the high genomic complexity that is so frequent in this type of lymphoma. 95

As discussed, BCL6 is a strong repressor of many genes, including BCL2 and MYC. 44,68,70 Therefore, both constitutive activation of MYC and BCL2 by chromosomal translocation might be of advantage for BCL6 ? tumor cells. In reverse, because DNA damage induced by MYC can repress BCL6 expression, constitutive activation of BCL6 by a translocation might be of selective advantage for MYC-overexpressing tumor cells.

For CCND1 and MYC, the synergy may be based on the fact that cyclin D mediates G 1 -S phase transition. Activation of MYC may bring the cells in an advantageous metabolic state, allowing cells to progress further. This synergy has also been shown in CCND1-MYC transgenic mice. 96,97 Indeed acquisition of a MYC translocation is associated with a dramatic morphologic change in MCL (blastic 98 or even mimicking BL 99 ).

Clinicopathologic aspects of mature DH B-cell lymphomas involving MYC +, BCL2 + ,

and BCL6 +

Classification

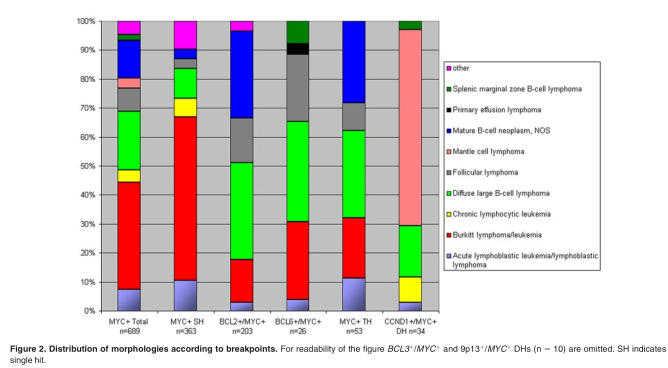

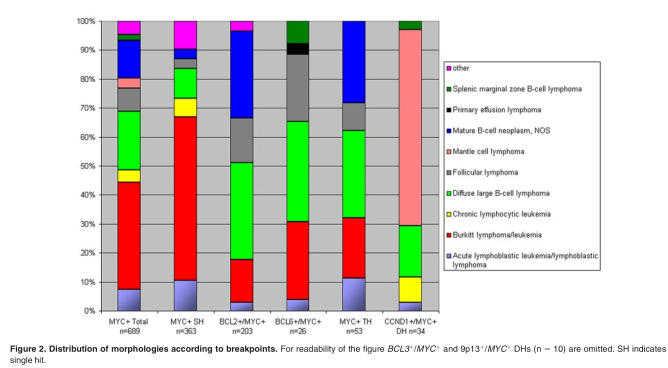

As can be concluded from the analysis of the Mitelman database 8 and the original publications therein, DH lymphomas show hetero-geneous morphologies, most of the BCL2 + /MYC+ and BCL6 +/ MYC + DH cases being classified as DLBCL or mature B-cell lymphoma NOS (Figure 2). Except for the BCL6 + /MYC + DH cases, 20% were classified as BL. Of note, the category of “mature B-cell neoplasm NOS,” was frequently called “Burkittlike lymphoma” in the past and therefore possibly was lumped with BL, also in the Mitelman database. 8 On the basis of these literature data and our own experience, there are no unique unifying morphologic features of DH lymphomas. Rare cases were classified as lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia. These cases express CD10 and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) and lack expression of immunoglobulins. 48,100,101 Intriguingly, at least some of these cases do not really represent a neoplasm of precursor B cells but B cells that may have reexpressed TdT, because they have accumulated somatic hypermutations, a hallmark of GC B cells. 102,103 Whatever the nature of these exceptional cases may be, many DH lymphoblastic cases in the Mitelman database 8 are incompletely documented without data on expression of TdT or CD34.

On the basis of the difficulties to classify many DH cases and because they represent a subset of highly aggressive lymphomas (see this and following sections), it was considered that these lymphomas, in particular the BCL2 +/MYC + DH cases, should be separated from other lymphomas. In the 2008 WHO classification, 6 these cases are therefore called “B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between DLBCLand BL.” Discussion is ongoing whether otherwise morphologically regular DLBCL with a BCL2 + /MYC + DH should be placed in this category as well. As discussed below, both molecular and clinical data indeed suggest this should be done.

Certainly not all DH lymphomas represent morphologic aggressive lymphomas. In the BCL2 + /MYC + group rare cases represented morphologic untransformed follicular lymphoma, whereas other cases had blastoid features or were classified as follicular lymphoma grade 3a or 3b. 14 In 3 studies that systematically addressed MYC rearrangements in follicular lymphoma, the frequency was 2%-8%. 104-106 However, all studies showed deficits in histology (grading, Ki67 proliferation index) or clinical follow-up. One interesting observation was that MYC translocation may be associated with a blastic/blastoid morphology of the tumor cells (4 of 7 cases being DH follicular lymphoma), 106 which is usually associated with progressive disease. The implications of the presence of MYC rearrangement at initial diagnosis in follicular lymphoma thus deserves further study.

Immunophenotype

We collected immunophenotypical data from larger studies on DH lymphoma. 10-15 Most lymphomas had a GC phenotype with expression of CD10 (107 of 122 cases; 88%) and BCL6 (45 of 60; 75%) and lack of MUM1/IRF4 (12 of 69; 17%). This corroborates the observation that BCL2 translocations are mainly found in GC type of DLBCL, and that also MYC translocations are associated with a GC molecular profile in DLBCL. 107,108 Most importantly, the BCL2 protein was detected in 101 of 106 cases (95%). The Ki67/MIB1 proliferation rate varied between 50% and 100% with a median of 90% in the 58 cases for which accurate data were given. Thus, although not very specific, coexpression of CD10, BCL6, BCL2, and a high Ki67 proliferation index might be used to select potential DH lymphomas in tumors morphologically diagnosed as DLBCL.

Gene expression profile

So far only 2 studies on BL and gray zone lymphomas between BL and DLBCL addressed gene expression specifically for BCL2 + /MYC + DH lymphomas. 109,110 In a collaborative study of the German network Molecular Mechanisms in Malignant Lymphoma (MMML) project on 220 aggressive B-cell lymphomas, 109 16 cases represented DH lymphomas with a BCL2 +/ MYC + , BCL6 + /MYC + DH or TH configuration. All cases except one with a borderline profile had a gene expression profile that was “intermediate between Burkitt lymphoma and DLBCL” or “non-BL.” With the use of a molecular algorithm in which the molecular profiles were constructed in a different way, the Lymphoma/Leukemia Molecular Profiling Project consortium investigated the gene expression profile in 3 BCL2 + /MYC + DH lymphomas. 110 Morphologically, these lymphomas had not been diagnosed as BLs but had a molecular BL score of 98% or 99% and thus were classified as discrepant lymphomas. These discrepant cases had much higher genomic imbalances than true BL (6.9 + 4.4 versus 1.5 +1.8 in BL), suggesting that they are nevertheless different from real BL. 111 Importantly, 6 “regular” DLBCLcases with a MYC breakpoint (no DH) did not have a BL type of gene expression in the Lymphoma/Leukemia Molecular Profiling Project study, indicating that some MYC translocations might be insufficient to enforce a full-blown MYC-driven gene expression program, probably because the partner is a non-IG gene locus with different regulatory properties than IG loci or because the genetic or cellular background interacts with the possibility to fully express a MYC program. 40 An additional interesting finding by the MMML consortium was that in 14 of the 35 MYC breakpoint-positive cases that lacked the molecular BL signature, a non-IG partner was involved in the MYC breakpoint. Thus, in particular the MMML study suggests that DH lymphomas are biologically and clinically different from both classical BL and DLBCL. In fact, they cannot be classified easily, probably because the profile has shifted toward molecular BLafter acquiring a MYC translocation.

Clinical aspects

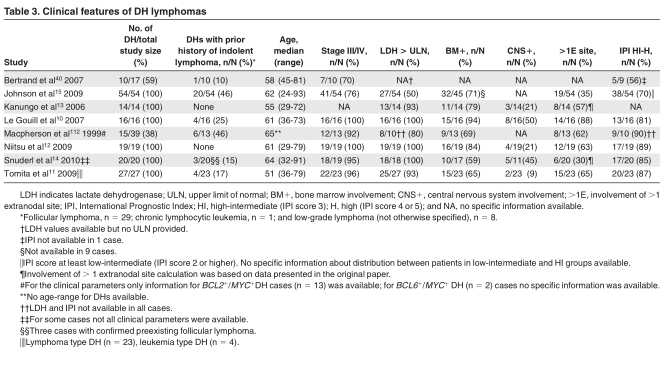

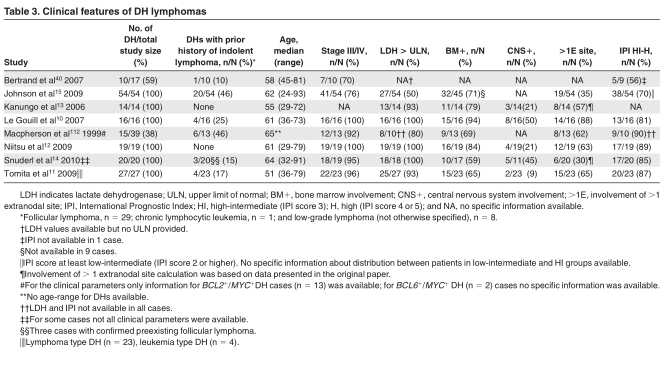

In this section we focus on DH lymphomas involving MYC, BCL2, and BCL6. We collected clinical features of DH cases from 8 studies with ? 10 DH cases and with sufficient clinical data (Table 3). 10-15,40,112 Median age for the DH lymphomas ranged from 51 to 65 years. DH lymphomas are extremely rare in children younger than 18 years of age. 113

Aprior history of indolent lymphoma was documented only in a minority of cases. In the majority of cases elevated lactate= dehydrogenase and an advanced stage of disease was reported. In addition patients often had extranodal involvement. The bone marrow and central nervous system (CNS) were most frequently involved, although the frequency of CNS involvement varied widely between studies (9%-50%). In addition, pleural effusions were commonly reported. 10-12 Most patients had a high-intermediate or high International Prognostic Index (IPI) risk profile (IPI score 3 or 4/5).

Therapy and outcome

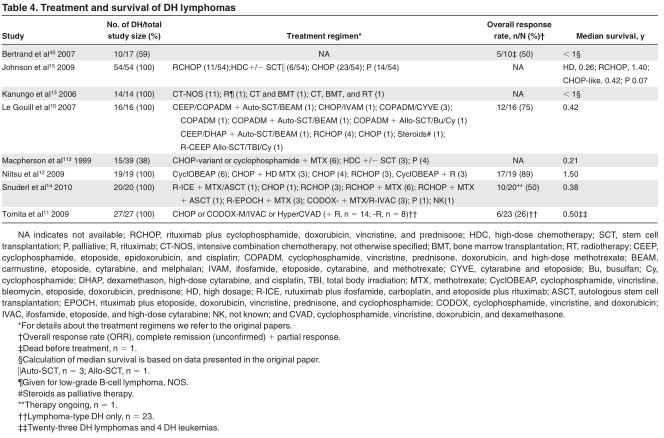

In Table 4, a summary is given for the most relevant published clinical studies in which patients with DH lymphoma could be identified. Patients were treated with a variety of regimens (includ- ing doxorubicin-based chemotherapy regimens as well as highdose chemotherapy regimens with stem cell transplantation). In some instances only palliative therapy was given. With these limitations taken into account, DH lymphomas generally tended to have a poor survival, with a median overall survival of only 0.2-1.5 years. 10-15,40,112

In a recent study on 303 patients with DLBCL treated with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone, 35 had a MYC rearrangement of which 27 (77%) were DH cases. 114 All MYC-rearranged cases had an inferior outcome, also compared with the individual IPI categories. Additional breakpoints of BCL2 or BCL6 had no significant additional effect on survival, but this may have been because only 8 of the 27 patients did not have a DH lymphoma. Few data are available for other treatment modalities. All 4 patients with DLBCL with a DH who received high-intensity chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, high-dose methotrexate/ifosfamide, etoposide, and high-dose cytarabine died within 5 months after the start of treatment. 115

How can the dismal outcome in DH lymphomas be explained?

Several biologic mechanisms may arise to explain the dismal outcome in patients with DH lymphoma:First, it could be that activation of MYC is directly responsible. However, the observation that adult patients with BL have a much more favorable outcome is against this hypothesis and suggests that additional factors are essential.

Second, the synergistic action of MYC and BCL2 might be responsible for this behavior. Observations in transgenic mice (see“Oncogenes involved in DH lymphomas” and “Timing and synergy of translocations in DH lymphomas”) as well as some clinical observations support this hypothesis. For instance in one report with relatively large numbers of cases and relatively homogeneous therapy the 19 BCL2 ? /MYC ? cases had a worse survival than the 24 patients with a single MYC ? or the 18 patients with a single BCL2 ? translocation, as well as all 333 patients with other DLBCL. 12

Third, it could be that other molecular features play an important role as well. DH lymphomas often have a complex karyotype with many additional genetic alterations, and the poor outcome may reflect many of these alterations.The role of genomic complexity as such is suggested by the studies of Hummel et al 109 and Seegmiller et al, 116 both indicating that the genomic complexity correlates with survival in lymphomas with a MYC rearrangement. Interestingly, on the basis of their biologic functions, it might be speculated that MYC and BCL2 themselves play a role in the generation of this genomic complexity.

Most clinical studies concerned BCL2 + /MYC + DH lymphomas, and only little can be concluded for BCL6 + /MYC + DH lymphomas, also because most of these lymphomas in fact might represent BCL2 + /BCL6 + /MYC + TH lymphomas. 11,117

Clinicopathologic aspects of other DH lymphomas

In the Mitelman database 8 as analyzed by us, 34 DH lymphoma cases had a CCND1 + /MYC + combination (Table 2; Figure 2). CCND1 + /MYC + DH cases accounted for 5% of all MCLs. Many of these cases were leukemic and had a blastoid, pleomorphic, or even a BL-like morphology. Perhaps because of the retained and easily detectable cyclin D1 protein expression in tissue sections, most of these cases were readily diagnosed as MCL.An overrepresentation of such cases in the database may have also occurred because leukemic MCLs are possibly more frequently karyotyped than nonleukemic MCLs, and most of these cases presented with overtly leukemic disease. Intriguingly, some CCND1 + /MYC + DH cases had aberrant expression of CD10 and BCL6, which parallels the observation that most MYC-rearranged DLBCLalso express CD10.

Because most cases were studied on leukemic cells, only few cases have been documented for the Ki67 proliferation index. 99,118,119 Six of 8 documented cases had a Ki67 index of > 75%, suggesting that MYC might confer an important additional proliferative boost to the tumor cells in which proliferation is a strong driving force. 120 Interestingly, a recent gene expression study of 65 MCL cases showed that high MYC expression is the most important factor for outcome but only marginally was associated with the Ki67 proliferation index, suggesting a role of MYC in the (TP53) DNA damage pathway rather than in the proliferation pathway. 121 As far as can be concluded from the reports, MCLs with involvement of 8q24 tend to have an aggressive clinical course, the average survival of CCND1 + /MYC + MCLbeing only 8 months. 119

The reported numbers of the rare other DH lymphomas involving BCL3 or other loci are too few to draw any conclusions.

One interesting feature that needs more attention is a subset of lymphomas in which 9p13 is involved, (see “Published DH

lymphomas” and supplemental Table 2).

DH lymphomas and "B-cell lymphomas,unclassifiable with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and Burkitt lymphoma”

According to the 2008 WHO classification, the category “B-cell lymphomas, unclassifiable with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and Burkitt lymphoma” 6 is a heterogeneous category of lymphomas that for biologic and clinical reasons should not be classified as BL lymphoma or DLBCL. It is meant as a temporary category, necessary until better discriminating criteria and more distinct categories of lymphomas are available. Apart from the DH lymphomas there are 3 other problematic issues with respect to the diagnosis of BL versus DLBCL that justified this category: First, the most problematic area is formed by non-DH lymphomas that are diagnosed as DLBCL but nonetheless share several morphologic and immunophenotypical features with BL,in particular a cohesive growth pattern, a very high Ki-67 proliferation index, and expression of GC associated proteins such as CD10. The dimension of this diagnostic problem is difficult to assess but certainly is different between pediatric and adult patients. Many of such cases in children contain an MYC-IG breakpoint, do not have any other breakpoint, and have a gene expression profile similar to BLand, therefore, probably should be better diagnosed as BL. 122 In contrast, for adult patients no data are available for large series of DLBCLs collected in population-based studies in which all ancillary tests to exclude BL or DH lymphomas have been applied. According to the Nordic Lymphoma Group, 123 which more or less reflects a population-based registry, 10% of all 185 DLBCL cases had a Ki-67 proliferation index of ? 90%. This should mean that after exclusion of DH lymphomas and DLBCL with a phenotype not compatible with BL, far ? 10% of all DLBCL are problematic in this respect. 109,124

Second, BL has a characteristic expression of CD20, CD10, BCL6 and the absence of BCL2 protein, whereas MUM1/IRF4 may be expressed at low levels. However, in ? 20% of all otherwise classical BLs some immunophenotypic abnormalities have been reported, for instance weak expression of BCL2 protein in 0%-20% 109,125 or aberrant expression of T-cell markers such as CD4 or CD5. 126 As already discussed in this review, such cases should only be accepted as BL after vigorous exclusion of a DH lymphoma.

Finally, in ~10% of all lymphomas that are otherwise indistinguishable from BL, including endemic and pediatric BLs, a MYC breakpoint is not detectable by current FISH methods. It might be considered to restrict the diagnosis of BL to cases with a proven MYC-IG breakpoint and to consign all other cases to the “intermediate” group. Likely, it is too early to do so because certain MYC breakpoints are missed with the current (FISH) methods and because in rare cases of BL a similar high MYC expression can be induced by down-regulation of miRNA-34B. 127

These dilemmas and the fact that many recent publications suggest that the presence of a MYC breakpoint in DLBCL, either or not involved in a DH, has an important prognostic value, 109,108,114,117,128,129 suggest that all aggressive mature B lymphomas should be systematically studied with ancillary methods, in particular FISH analysis, to provide the best possible diagnosis and therapeutic prospects.

Conclusions

DH and TH lymphomas are B-cell lymphomas characterized by a recurrent chromosomal translocation in combination with a MYC/ 8q24 breakpoint, the latter mostly as a secondary event involved in transformation. The compiled cytogenetic and FISH data strongly suggest that many lymphomas other than BL with a MYC breakpoint represent DH lymphomas. This implies that the studies that only focused on the effect of MYC breakpoints in DLBCL have to be reconsidered. Most DHs have a BCL2 + /MYC + combination, and most BCL6 + /MYC + DH lymphomas represent BCL2 + /BCL6 + / MYC + TH lymphomas. CCND1 + /MYC + DH lymphomas may be more frequent than anticipated and should receive more attention.

In view of the frequency of these aberrations and their clinical effect, it seems timely to test all aggressive B-cell lymphomas, including the MCLs with a high-proliferation index or blastic morphology, for MYC (and MYC-IG) breakpoints by FISH. In selected cases BCL2 and BCL6 FISH tests should be performed as well, for instance in those cases with a MYC breakpoint and concomitant BCL2 protein expression. A BCL2 + /MYC + DH lymphoma should be considered in all aggressive and highly proliferating B-cell lymphomas with a distinct GC B phenotype in combination with BCL2 expression, in particular when the patient presents with extensive disease, including bone marrow or CNS involvement or both. However. these parameters are insufficient to identify all cases.Moreover,individual morphologic and immunophenotypical parameters may have a low reproducibility. Although we realizethat detection of MYC, BCL2, and BCL6 breakpoints does not reflect all biologic aspects of these complex tumors, we suggest to perform these assays until more biologic data and better tests become available. Patients with DH lymphoma generally have rapidly progressive disease and a dismal outcome, even with high-intensity chemotherapy. The course of disease might reflect not only the synergistic actions of the ? 2 oncogenes involved but also the high genomic complexity in most of these tumors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Itziar Salaverria for critically reading the manuscript. This work was supported by the Deutsche Krebshilfe (Network Project “Molecular Mechanisms in Malignant Lymhpoma” [R.S.]) and BMBF (Network Project “Ha ¨matoSys” [R.S.]). S.M.A. is a fellow oftheJunior-Scientific-Masterclass-UMCGMD-PhDprogram.

Authorship

Contribution: S.M.A. performed literature and database searches and wrote the manuscript; R.S. contributed to the design and supervised the cytogenetic/molecular investigations; E.S. contributed to the scientific cytogenetic/molecular part of the manuscript; G.W.v.I. contributed to the design of the manuscript and wrote parts of the manuscript; H.C.K.-N. and E.-J.B. contributed to the design of the manuscript; P.M.K. contributed to the design of the manuscript and wrote parts of it.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for E.-J.B. is Department of Surgery, Maasstad Hospital, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Correspondence: Sieste M. Aukema, Department of Pathology and Medical Biology, University Medical Center Groningen, Hanzeplein 1, 9700 RB Groningen, The Netherlands; e-mail: s.m.aukema@student.rug.nl.

References

1. BloomfieldCD,ArthurDC,FrizzeraG,LevineEG, PetersonBA,GajlPeczalskaKJ.Nonrandom chromosome abnormalities in lymphoma.CancerRes. 1983;43(6):2975-2984.

2. Yunis JJ, Oken MM, TheologidesA, Howe RB, Kaplan ME. Recurrent chromosomal defects are found in most patients with non-Hodgkin’s-lymphoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1984;13(1):17-28.

3. Offit K, Jhanwar SC, Ladanyi M, Filippa DA, Chaganti RS. Cytogenetic analysis of 434 consecutively ascertained specimens of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: correlations between recurrent aberrations, histology, and exposure to cytotoxic treatment. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1991;3(3):189-201.

4. Siebert R. Mature B- and T-cell neoplasms and Hodgkin lymphomas. In: Heim S, Mitelman F, eds. Cancer Cytogenetics. New York, NY: WileyBlackwell; 2009.

5. Siebert R, RosenwaldA, Staudt LM, Morris SW. Molecular features of B-cell lymphoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2001;13(5):316-324.

6. Kluin PM, Harris NL, Stein H, et al. B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and Burkitt lymphoma. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France, IARC; 2008.

7. Biagi JJ, Seymour JF. Insights into the molecular pathogenesis of follicular lymphoma arising from analysis of geographic variation. Blood. 2002; 99(12):4265-4275.

8. Mitelman F Johansson B Mertens F, eds. Mitelman Database of ChromosomeAberrations and Gene Fusions in Cancer (February 2010). http://cgap.nci.nih.gov/Chromosomes/Mitelman.Accessed September 2, 2010.

9. Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Stein H, et al.Arevised Eu- ropean-American classification of lymphoid neoplasms: a proposal from the International Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 1994;84(5):1361-1392.

10. Le Gouill S, Talmant P, Touzeau C, et al. The clinical presentation and prognosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with t(14;18) and 8q24/c-MYC rearrangement. Haematologica. 2007;92(10): 1335-1342.

11. Tomita N, Tokunaka M, Nakamura N, et al. Clinicopathological features of lymphoma/leukemia

patients carrying both BCL2 and MYC translocations. Haematologica. 2009;94(7):935-943.

12. Niitsu N, Okamoto M, Miura I, Hirano M. Clinical features and prognosis of de novo diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with t(14;18) and 8q24/c-MYC translocations. Leukemia. 2009;23(4):777-783.

13. KanungoA, Medeiros LJ,Abruzzo LV, Lin P. Lym- phoid neoplasms associated with concurrent t(14;18) and 8q24/c-MYC translocation generally have a poor prognosis. Mod Pathol. 2006;19(1):25-33.

14. Snuderl M, Kolman OK, Chen YB, et al. B-cell lymphomas with concurrent IGH-BCL2 and MYC rearrangements are aggressive neoplasms with clinical and pathologic features distinct from Burkitt lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(3):327-340.

15. Johnson NA, Savage KJ, Ludkovski O, et al. Lymphomas with concurrent BCL2 and MYC translocations: the critical factors associated with survival. Blood. 2009;114(11):2273-2279.

16. GabreaA, Leif Bergsagel P, Michael Kuehl W.Distinguishing primary and secondary translocations in multiple myeloma. DNA Repair. 2006;5(9-10):1225-1233.

17. Bergsagel PL, Kuehl WM. Chromosome translocations in multiple myeloma. Oncogene. 2001;20(40):5611-5622.

18. ValeraA, Balague O, Colomo L, et al. IG/MYC

rearrangements are the main cytogenetic alteration in plasmablastic lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(11):1686-1694.

19. Avet-Loiseau H. Reply to: Comment to: The clinical presentation and prognosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with t(14;18) and 8q24/c-MYY rearrangement. Haematologica. 2007; 92(10):1335-1342. Haematologica. 2008;93(7):e54.

20. Bertrand P, Maingonnat C, Ruminy P, Tilly H,Bastard C. Comment to: The clinical presentation and prognosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with t(14;18) and 8q24/c-MYC rearrangement. Haematologica. 2007; 92(10):13351342. Haematologica. 2008;93(7):e53.

21. Dang CV, O’Donnell KA, Zeller KI, Nguyen T, Osthus RC, Li F. The c-Myc target gene network. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16(4):253-264.

22. Blackwood EM, Eisenman RN. Max: a helix-loop-helix zipper protein that forms a sequence-specific DNA-binding complex with Myc. Science. 1991;251(4998):1211-1217.

23. Blackwell TK, Kretzner L, Blackwood EM, Eisenman RN, Weintraub H. Sequence-specific DNAbinding by the c-Myc protein. Science. 1990; 250(4984):1149-1151.

24. Gu W, Cechova K, Tassi V, Dalla-Favera R. Opposite regulation of gene transcription and cell proliferation by c-Myc and Max. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(7):2935-2939.

25. Shim H, Dolde C, Lewis BC, et al. c-Myc transactivation of LDH-A: implications for tumor metabolism and growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997; 94(13):6658-6663.

26. Robertus JL, Kluiver J, Weggemans C, et al. MiRNAprofiling in B non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a MYC-related miRNAprofile characterizes Burkitt lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2010;149(6):896-899.

27. Chang TC, Yu D, Lee YS, et al. Widespread microRNArepression by Myc contributes to tumorigenesis. Nat Genet. 2008;40(1):43-50.

28. O’Donnell KA, Wentzel EA, Zeller KI, Dang CV, Mendell JT. c-Myc-regulated microRNAs modulate E2F1 expression. Nature. 2005;435(7043):839-843.

29. Klein U, Tu Y, Stolovitzky GA, et al. Transcriptional analysis of the B cell germinal center reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(5):2639-2644.

30. Klapproth K, Wirth T.Advances in the understanding of MYC-induced lymphomagenesis. Br J Haematol. 2010;149(4):484-497.

31. RamiroAR, Jankovic M, Eisenreich T, et al.AID is required for c-myc/IgH chromosome translocations in vivo. Cell. 2004;118(4):431-438.

32. Dorsett Y, Robbiani DF, Jankovic M, ReinaSan-Martin B, Eisenreich TR, Nussenzweig MC. Arole forAID in chromosome translocations between c-myc and the IgH variable region. J Exp Med. 2007;204(9):2225-2232.

33. Robbiani DF, Bunting S, Feldhahn N, et al.AID produces DNAdouble-strand breaks in non-Ig genes and mature B cell lymphomas with reciprocal chromosome translocations. Mol Cell. 2009; 36(4):631-641.

34. Robbiani DF, BothmerA, Callen E, et al.AID is required for the chromosomal breaks in c-myc that lead to c-myc/IgH translocations. Cell. 2008; 135(6):1028-1038.

35. Guikema JE, Schuuring E, Kluin PM. Structure and consequences of IGH switch breakpoints in Burkitt lymphoma. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2008;(39):32-36.

36. Prochownik EV. c-Myc: linking transformation and genomic instability. Curr Mol Med. 2008;8(6): 446-458.

37. Janz S. Genetic and environmental cofactors of Myc translocations in plasma cell tumor development in mice. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2008; (39):37-40.

38. Muller JR, Janz S, Goedert JJ, Potter M, Rabkin CS. Persistence of immunoglobulin heavy chain/c-myc recombination-positive lymphocyte clones in the blood of human immunodeficiency virus-infected homosexual men. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(14):6577-6581.

39. RoschkeV,KopantzevE,DertzbaughM,RudikoffS. Chromosomal translocations deregulating c-myc are

associated with norma limmune responses.Oncogene.1997;14(25):3011-3016.

40. Bertrand P, Bastard C, Maingonnat C, et al. Mapping of MYC breakpoints in 8q24 rearrangements involving non immunoglobulin partners in B-cell lymphomas. Leukemia. 2007;21(3):515-523.

41. Tsujimoto Y, Finger LR, Yunis J, Nowell PC, Croce CM. Cloning of the chromosome breakpoint of neoplastic B cells with the t(14;18) chromosome translocation. Science. 1984;226(4678):

1097-1099.

42. Graninger WB, Seto M, Boutain B, Goldman P, Korsmeyer SJ. Expression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-2-Ig fusion transcripts in normal and neoplastic cells. J Clin Invest. 1987;80(5):1512-1515.

43. Saito M, Novak U, Piovan E, et al. BCL6 suppression of BCL2 via Miz1 and its disruption in diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(27):11294-11299.

44. Ci W, Polo JM, Cerchietti L, et al. The BCL6 transcriptional program features repression of multiple oncogenes in primary B cells and is deregulated in DLBCL. Blood. 2009;113(22):5536-5548.

45. Seto M, Jaeger U, Hockett RD, et al.Alternative promoters and exons, somatic mutation and deregulation of the Bcl-2-Ig fusion gene in lymphoma. EMBO J. 1988;7(1):123-131.

46. Wang Q, Gao F, May WS, Zhang Y, Flagg T, Deng X. Bcl2 negatively regulates DNA doublestrand-break repair through a nonhomologous end-joining pathway. Mol Cell. 2008;29(4): 488-498.

47. Fenton JA, Vaandrager JW,Aarts WM, et al. Follicular lymphoma with a novel t(14;18) breakpoint involving the immunoglobulin heavy chain switch mu region indicates an origin from germinal center B cells. Blood. 2002;99(2):716-718.

48. De Jong D, Voetdijk BM, Beverstock GC, van Ommen GJ, Willemze R, Kluin PM.Activation of the c-myc oncogene in a precursor-B-cell blast crisis of follicular lymphoma, presenting as composite lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(21):

1373-1378.

49. Tsujimoto Y, Gorham J, Cossman J, Jaffe E, Croce CM. The t(14;18) chromosome translocations involved in B-cell neoplasms result from mistakes in VDJ joining. Science. 1985;

229(4720):1390-1393.

50. TsaiAG, Lu H, Raghavan SC, Muschen M, Hsieh CL, Lieber MR. Human chromosomal translocations at CpG sites and a theoretical basis for their lineage and stage specificity. Cell.

2008;135(6):1130-1142.

51. Jager U, Bocskor S, Le T, et al. Follicular lymphomas’ BCL-2/IgH junctions contain templated nucleotide insertions: novel insights into the mechanism of t(14;18) translocation. Blood. 2000; 95(11):3520-3529.

52. Nadel B, Marculescu R, Le T, Rudnicki M, Bocskor S, Jager U. Novel insights into the mechanism of t(14;18)(q32;q21) translocation in follicular lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2001;42(6):1181-1194.

53. Wang JH, Gostissa M, Yan CT, et al. Mechanisms promoting translocations in editing and switching peripheral B cells. Nature. 2009;460(7252): 231-236.

54. Wang JH,Alt FW, Gostissa M, et al. Oncogenic transformation in the absence of Xrcc4 targets peripheral B cells that have undergone editing and switching. J Exp Med. 2008;205(13): 3079-3090.

55. McDonnell TJ, Deane N, Platt FM, et al. bcl-2-immunoglobulin transgenic mice demonstrate extended B cell survival and follicular lymphoproliferation. Cell. 1989;57(1):79-88.

56. Nunez G, Seto M, Seremetis S, et al. Growthand tumor-promoting effects of deregulated BCL2 in human B lymphoblastoid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86(12):4589-4593.

57. Limpens J, Stad R, Vos C, et al. Lymphoma-associated translocation t(14;18) in blood B cells of normal individuals. Blood. 1995;85(9):2528-2536.

58. Roulland S, Lebailly P, Lecluse Y, Heutte N, Nadel B, Gauduchon P. Long-term clonal persistence and evolution of t(14;18)-bearing B cells in healthy individuals. Leukemia. 2006;20(1): 158-162.

59. Roulland S, Lebailly P, Gauduchon P. Correspondence re: Welzel et al, Cancer Res 2001, 61(4): 1629-1636. Cancer Res. 2003;63(7):1722-1723.

60. Roulland S, Navarro JM, Grenot P, et al. Follicular lymphoma-like B cells in healthy individuals: a novel intermediate step in early lymphomagenesis. J Exp Med. 2006;203(11):2425-2431.

61. Cong P, Raffeld M, Teruya-Feldstein J, Sorbara L, Pittaluga S, Jaffe ES. In situ localization of follicular lymphoma: description and analysis by laser capture microdissection. Blood. 2002;99(9):3376-3382.

62. StrasserA, HarrisAW, Bath ML, Cory S. Novel primitive lymphoid tumours induced in transgenic mice by cooperation between myc and bcl-2. Nature. 1990;348(6299):331-333.

63. McDonnell TJ, Korsmeyer SJ. Progression from lymphoid hyperplasia to high-grade malignant lymphoma in mice transgenic for the t(14; 18). Nature. 1991;349(6306):254-256.

64. Cattoretti G, Chang CC, Cechova K, et al. BCL-6 protein is expressed in germinal-center B cells. Blood. 1995;86(1):45-53.

65. Onizuka T, Moriyama M, Yamochi T, et al. BCL-6 gene product, a 92- to 98-kD nuclear phosphoprotein, is highly expressed in germinal center B cells and their neoplastic counterparts. Blood. 1995;86(1):28-37.

66. Ye BH, Cattoretti G, Shen Q, et al. The BCL-6 proto-oncogene controls germinal-centre formation and Th2-type inflammation. Nat Genet. 1997; 16(2):161-170.

67. DentAL, ShafferAL, Yu X,Allman D, Staudt LM. Control of inflammation, cytokine expression, and germinal center formation by BCL-6. Science. 1997;276(5312):589-592.

68. Basso K, Saito M, Sumazin P, et al. Integrated biochemical and computational approach identifies BCL6 direct target genes controlling multiple pathways in normal germinal center B cells.

Blood. 2010;115(5):975-984.

69. Parekh S, Polo JM, Shaknovich R, et al. BCL6 programs lymphoma cells for survival and differentiation through distinct biochemical mechanisms. Blood. 2007;110(6):2067-2074.

70. ShafferAL, Yu X, He Y, Boldrick J, Chan EP, Staudt LM. BCL-6 represses genes that function in lymphocyte differentiation, inflammation, and cell cycle control. Immunity. 2000;13(2):199-212.

71. Kuo TC, ShafferAL, Haddad J Jr, Choi YS, Staudt LM, Calame K. Repression of BCL-6 is required for the formation of human memory B cells in vitro. J Exp Med. 2007;204(4):819-830.

72. Tunyaplin C, ShafferAL,Angelin-Duclos CD, Yu X, Staudt LM, Calame KL. Direct repression of prdm1 by Bcl-6 inhibits plasmacytic differentiation. J Immunol. 2004;173(2):1158-1165.

73. Phan RT, Dalla-Favera R. The BCL6 proto-oncogene suppresses p53 expression in germinalcentre B cells. Nature. 2004;432(7017):635-639.

74. Ye BH, Chaganti S, Chang CC, et al. Chromosomal translocations cause deregulated BCL6 expression by promoter substitution in B cell lymphoma. EMBO J. 1995;14(24):6209-6217.

75. Saito M, Gao J, Basso K, et al.Asignaling pathway mediating downregulation of BCL6 in germinal center B cells is blocked by BCL6 gene alterations in B cell lymphoma. Cancer Cell. 2007;

12(3):280-292.

76. Cattoretti G, Pasqualucci L, Ballon G, et al. Deregulated BCL6 expression recapitulates the

pathogenesis of human diffuse large B cell lymphomas in mice. Cancer Cell. 2005;7(5):445-455.

77. Vaandrager JW, Schuuring E, Zwikstra E, et al. Direct visualization of dispersed 11q13 chromosomal translocations in mantle cell lymphoma by multicolor DNAfiber fluorescence in situ hybridization. Blood. 1996;88(4):1177-1182.

78. Avet-Loiseau H, Li JY, Facon T, et al. High incidence of translocations t(11;14)(q13;q32) and t(4;14)(p16;q32) in patients with plasma cell malignancies. Cancer Res. 1998;58(24):5640-5645.

79. Au WY, Gascoyne RD, Viswanatha DS, Connors JM, Klasa RJ, Horsman DE. Cytogenetic analysis in mantle cell lymphoma: a review of 214 cases. Leuk Lymphoma. 2002;43(4):783-791.

80. Salaverria I, Espinet B, CarrioA, et al. Multiple recurrent chromosomal breakpoints in mantle cell lymphoma revealed by a combination of molecular cytogenetic techniques. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47(12):1086-1097.

81. de Boer CJ, Kluin-Nelemans JC, Dreef E, et al. Involvement of the CCND1 gene in hairy cell leukemia. Ann Oncol. 1996;7(3):251-256.

82. Welzel N, Le T, Marculescu R, et al. Templated nucleotide addition and immunoglobulin JH-gene utilization in t(11;14) junctions: implications for the mechanism of translocation and the origin of mantle cell lymphoma. Cancer Res. 2001;61(4):

1629-1636.

83. Lecluse Y, Lebailly P, Roulland S, GacAC, Nadel B, Gauduchon P. t(11;14)-positive clones can persist over a long period of time in the peripheral blood of healthy individuals. Leukemia.

2009;23(6):1190-1193.

84. Janssen JW, Vaandrager JW, Heuser T, et al. Concurrent activation of a novel putative transforming gene, myeov, and cyclin D1 in a subset of multiple myeloma cell lines with t(11;14)(q13; q32). Blood. 2000;95(8):2691-2698.

85. Bhatia K, Huppi K, McKeithan T, Siwarski D, Mushinski JF, Magrath I. Mouse bcl-3: cDNA structure, mapping and stage-dependent expression in B lymphocytes. Oncogene. 1991;6(9):1569-1573.

86. Franzoso G, Carlson L, Scharton-Kersten T, et al. Critical roles for the Bcl-3 oncoprotein in T cell mediated immunity, splenic microarchitecture, and germinal center reactions. Immunity. 1997; 6(4):479-490.

87. Ohno H, Takimoto G, McKeithan TW. The candidate proto-oncogene bcl-3 is related to genes implicated in cell lineage determination and cell cycle control. Cell. 1990;60(6):991-997.

88. Chapiro E, Radford-Weiss I, Bastard C, et al. The most frequent t(14;19)(q32;q13)-positive B-cell

malignancy corresponds to an aggressive subgroup of atypical chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2008;22(11):2123-2127.

89. Martin-Subero JI, Ibbotson R, Klapper W, et al.A comprehensive genetic and histopathologic analysis identifies two subgroups of B-cell malignancies carrying a t(14;19)(q32;q13) or variant BCL3 translocation. Leukemia. 2007;21(7):1532-1544.

90. McKeithan TW, Rowley JD, Shows TB, Diaz MO. Cloning of the chromosome translocation breakpoint junction of the t(14;19) in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987; 84(24):9257-9260.

91. Ohno H, Doi S, Yabumoto K, Fukuhara S, McKeithan TW. Molecular characterization of the t(14;19)(q32;q13) translocation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 1993;7(12):2057-2063.

92. McKeithan TW, Takimoto GS, Ohno H, et al. BCL3 rearrangements and t(14;19) in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and other B-cell malignancies: a molecular and cytogenetic study. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1997;20(1):64-72.

93. Ong ST, Hackbarth ML, Degenstein LC, Baunoch DA,Anastasi J, McKeithan TW. Lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and altered immunoglobulin production in BCL3 transgenic mice. Oncogene. 1998;16(18):2333-2343.

94. De Jong D, Voetdijk BM, van Ommen GJ, Kluin-Nelemans JC, Beverstock GC, Kluin PM. Translocation t(14;18) in B cell lymphomas as a cause for defective immunoglobulin production. J Exp Med. 1989;169(3):613-624.

95. Boerma EG, Siebert R, Kluin PM, Baudis M. Translocations involving 8q24 in Burkitt lymphoma and other malignant lymphomas: a historical review of cytogenetics in the light of today’s knowledge. Leukemia. 2009;23(2):225-234.

96. Bodrug SE, Warner BJ, Bath ML, Lindeman GJ, HarrisAW,Adams JM. Cyclin D1 transgene impedes lymphocyte maturation and collaborates in lymphomagenesis with the myc gene. EMBO J. 1994;13(9):2124-2130.

97. Lovec H, GrzeschiczekA, Kowalski MB, Moroy T. Cyclin D1/bcl-1 cooperates with myc genes in the generation of B-cell lymphoma in transgenic mice. EMBO J. 1994;13(15):3487-3495.

98.AuWY,HorsmanDE,ViswanathaDS,ConnorsJM,KlasaRJ,GascoyneRD.8q24 translocationsin blastic transformation of mantle cell lymphoma. Haematologica.2000;85(11):1225-1227.

99.FeltenCL,StephensonCF,OrtizRO,HertzbergL.Burkitt transformation of mantle cell lymphoma.Leuk Lymphoma.2004;45(10):2143-2147.

100. Gauwerky CE, Hoxie J, Nowell PC, Croce CM. Pre-B-cell leukemia with a t(8; 14) and a t(14; 18) translocation is preceded by follicular lymphoma. Oncogene. 1988;2(5):431-435.

101. Young KH, Xie Q, Zhou G, et al. Transformation of follicular lymphoma to precursor B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma with c-myc gene rearrangement as a critical event. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008; 129(1):157-166.

102. Hardianti MS, Tatsumi E, Syampurnawati M, et al. Presence of somatic hypermutation and activation-induced cytidine deaminase in acute lymphoblastic leukemia L2 with t(14;18)(q32;q21). Eur J Haematol. 2005;74(1):11-19.

103. Kobrin C, Cha SC, Qin H, et al. Molecular analysis of light-chain switch and acute lymphoblastic leukemia transformation in two follicular lymphomas: implications for lymphomagenesis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47(8):1523-1534.

104. Christie L, Kernohan N, Levison D, et al. C-MYC translocation in t(14;18) positive follicular lymphoma at presentation:An adverse prognostic indicator? Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49(3):470-476.

105. Yano T, Jaffe ES, Longo DL, Raffeld M. MYC rearrangements in histologically progressed follicular lymphomas. Blood. 1992;80(3):758-767.

106. MohamedAN, Palutke M, Eisenberg L,Al KatibA. Chromosomal analyses of 52 cases of follicular lymphoma with t(14;18), including blastic/blastoid variant. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2001;126(1): 45-51.

107. Lenz G, Wright GW, Emre NC, et al. Molecular subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma arise by distinct genetic pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(36):13520-13525.

108. Klapper W, Stoecklein H, Zeynalova S, et al. Structural aberrations affecting the MYC locus indicate a poor prognosis independent of clinical risk factors in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas treated within randomized trials of the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Study Group (DSHNHL). Leukemia. 2008;22(12): 2226-2229.

109. Hummel M, Bentink S, Berger H, et al.Abiologic definition of Burkitt’s lymphoma from transcriptional and genomic profiling. N Engl J Med. 2006; 354(23):2419-2430.

110. Dave SS, Fu K, Wright GW, et al. Molecular diagnosis of Burkitt’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2006; 354(23):2431-2442.

111. Salaverria I, ZettlA, Bea S, et al. Chromosomal alterations detected by comparative genomic hybridization in subgroups of gene expression-defined Burkitt’s lymphoma. Haematologica. 2008; 93(9):1327-1334.

112. Macpherson N, Lesack D, Klasa R, et al. Small noncleaved, non-Burkitt’s (Burkit-Like) lymphoma: cytogenetics predict outcome and reflect clinical presentation. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(5): 1558-1567.

113. Oschlies I, Salaverria I, Mahn F, et al. Pediatric follicular lymphoma–a clinico-pathological study of a population-based series of patients treated within the Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma–Berlin-Frankfurt-Munster (NHL-BFM) multicenter trials.

Haematologica. 2010;95(2):253-259.

114. Barrans S, Crouch S, SmithA, et al. Rearrangement of MYC is associated with poor prognosis in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated in the era of rituximab. J Clin Oncol. 2010; 28(20):3360-3365.

115. Mead GM, Barrans SL, Qian W, et al.Aprospective clinicopathologic study of dose-modified CODOX-M/IVAC in patients with sporadic Burkitt lymphoma defined using cytogenetic and immunophenotypic criteria (MRC/NCRI LY10 trial). Blood. 2008;112(6):2248-2260.

116. SeegmillerAC, Garcia R, Huang R, MalekiA, Karandikar NJ, Chen W. Simple karyotype and bcl-6 expression predict a diagnosis of Burkitt lymphoma and better survival in IG-MYC rearranged high-grade B-cell lymphomas. Mod Pathol. 2010;23(7):909-920.

117. Niitsu N, Okamoto M, Miura I, Hirano M. Clinical significance of 8q24/c-MYC translocation in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Sci. 2009; 100(2):233-237.

118. Hao S, Sanger W, Onciu M, Lai R, Schlette EJ, Medeiros LJ. Mantle cell lymphoma with 8q24 chromosomal abnormalities: a report of 5 cases with blastoid features. Mod Pathol. 2002;15(12): 1266-1272.

119. Reddy K,Ansari-Lari M, Dipasquale B. Blastic mantle cell lymphoma with a Burkitt translocation. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49(4):740-750.

120. RosenwaldA, Wright G, WiestnerA, et al. The proliferation gene expression signature is a quantitative integrator of oncogenic events that predicts survival in mantle cell lymphoma. Cancer Cell. 2003;3(2):185-197.

121. Kienle D, Katzenberger T, Ott G, et al. Quantitative gene expression deregulation in mantle-cell lymphoma: correlation with clinical and biologic factors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(19):2770-2777.

122. Klapper W, Szczepanowski M, Burkhardt B, et al. Molecular profiling of pediatric mature B-cell lymphoma treated in population-based prospective clinical trials. Blood. 2008;112(4):1374-1381.

123. Jerkeman M,Anderson H, Dictor M, Kvaloy S, Akerman M, Cavallin-Stahl E.Assessment of biological prognostic factors provides clinically relevant information in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma–a Nordic Lymphoma Group study. Ann Hematol. 2004;83(7):414-419.

124. Haralambieva E, Boerma EJ, van Imhoff GW, et al. Clinical, immunophenotypic, and genetic analysis of adult lymphomas with morphologic features of Burkitt lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(8):1086-1094.

125. Chuang SS, Ye H, Du MQ, et al. Histopathology and immunohistochemistry in distinguishing Burkitt lymphoma from diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with very high proliferation index and with or without a starry-sky pattern: a comparative study with EBER and FISH. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128(4): 558-564.

126. Lin CW, O’Brien S, Faber J, et al. De novo CD5? Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia. Am J Clin Pathol. 1999;112(6):828-835.

127. Leucci E, Cocco M, OnnisA, et al. MYC translocation-negative classical Burkitt lymphoma cases: an alternative pathogenetic mechanism involving miRNAderegulation. J Pathol. 2008; 216(4):440-450.

128. Savage KJ, Johnson NA, Ben Neriah S, et al. MYC gene rearrangements are associated with a poor prognosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients treated with R-CHOP chemotherapy. Blood. 2009;114(17):3533-3537.

129. Yoon SO, Jeon YK, Paik JH, et al. MYC translocation and an increased copy number predict poor prognosis in adult diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), especially in germinal centrelike B cell (GCB) type. Histopathology. 2008;53(2):205-217.

130. Obermann EC, Csato M, Dirnhofer S, TzankovA. Aberrations of the MYC gene in unselected cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma are rare and unpredictable by morphological or immunohisto chemical assessment. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62(8):

754-756.

131. Tibiletti MG, Martin V, Bernasconi B, et al. BCL2, BCL6, MYC, MALT 1, and BCL10 rearrangements in nodal diffuse large B-cell lymphomas: a multicenter evaluation of a new set of fluorescent in situ hybridization probes and correlation with

clinical outcome. Hum Pathol. 2009;40(5): 645-652.

132. Copie-Bergman C, Gaulard P, Leroy K, et al. Immuno-fluorescence in situ hybridization index predicts survival in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP: a GELA study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(33):5573-5579.

133. van Imhoff GW, Boerma EJ, van der Holt B, et al. Prognostic impact of germinal center-associated proteins and chromosomal breakpoints in poorrisk diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(25):4135-4142.